New Orleans’ Lee Ledbetter Makes Design Magic by Mixing Past and Present

Introspective Magazine / March 24, 2019

BY Linda O’Keeffe

The Louisiana-born and -bred architect talks to 1stdibs about the art of making timeless places that matter.

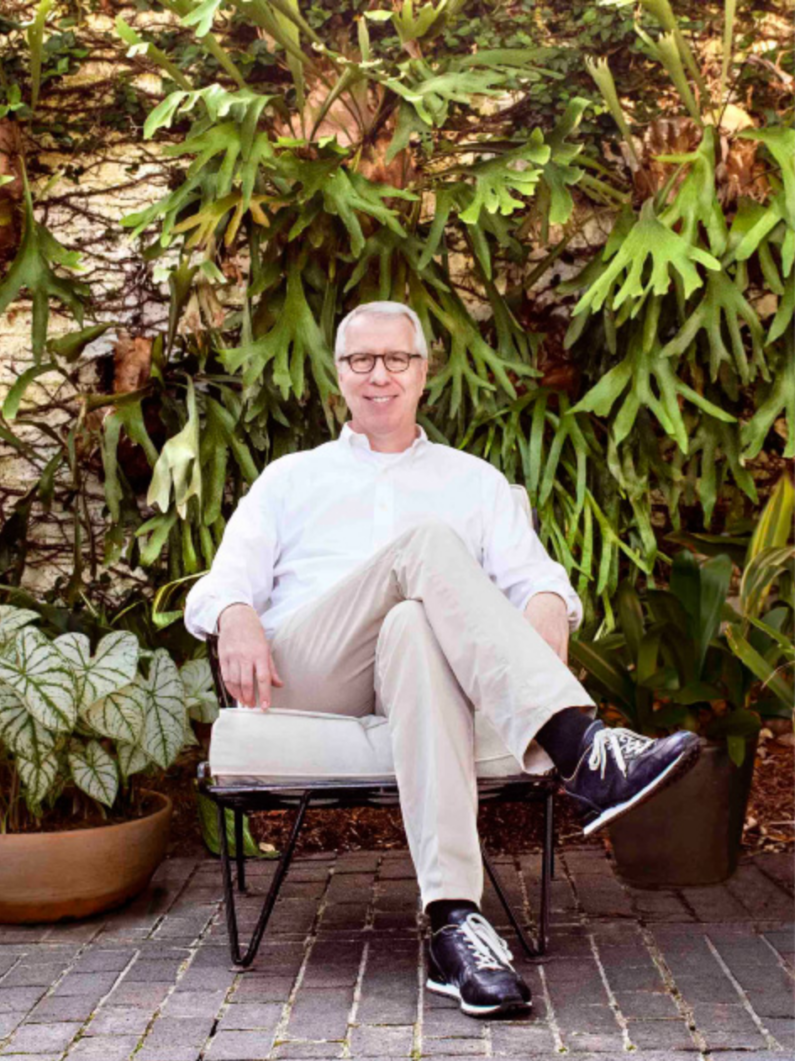

A new Rizzoli monograph from New Orleans–based architect and interior designer Lee Ledbetter shows off 13 of his residential projects (portrait by Henrik A. Knudsen). Top: In the den of a home in the Crescent City’s Garden District, Ledbetter flanked a custom mohair sofa with a pair of Edward Wormley swivel chairs and a pair of Harvey Probber bolster chairs (all photos by Pieter Estersohn, unless otherwise noted).

Lee Ledbetter defies categorization. An architect with serious credentials — he studied at the University of Virginia and Princeton and worked at Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, Michael Graves and Gwathmey Siegel — he refuses to be confined to one aesthetic. His houses are born from the immediate environment and greater region in which they are situated and react to local vernaculars rather than reject them. When Ledbetter dons his preservationist hat, he respects a building’s previous lives even as he brings them into dialogue with the present. The results are refreshingly unique.

His fluency in modernism and classicism, his reverence for historical precedents, his cosmopolitan perspective and willingness to submit to the pull of his Louisiana heritage — he was born and raised in the state and has run his studio from New Orleans for two decades — all qualify him as one of the country’s most accomplished, innovative and successful architectural practitioners.

Ledbetter also decorates his clients homes, creating layouts in which he often juxtaposes mid-century furniture by T. H. Robsjohn-Gibbings, Edward Wormley, Milo Baughman, William Haines and Harvey Probber with timeworn antique rugs, graphic textiles and muscular ceramics. He’s open to all periods, proclivities and provenances, and so his decor can be spare or sumptuous, laid-back or exuberant. He’s as likely to showcase contemporary art with a minimalist, Halston-inspired palette as he is to layer antiques with patterned textiles and wallpaper.

If Ledbetter has a signature, it’s the sense of spaciousness he injects into his rooms. His portfolio is full of wide thresholds, coffered ceilings, plays on scale, expansive color combinations and walls bathed in light. Many of his interiors are also characterized by a bias toward symmetry, the prominence of art (he’s both a trained painter and an avid collector) and a preference for comfort, elegance and panache.

Baker chairs in walnut surround a Matthew Hilton table in the dining area of the Garden District house. A large 19th-century giltwood mirror helps disperse light from a Lindsey Adelman chandelier and French contemporary brass sconces.

Ledbetter’s broad, spirited approach is on display in his recently released debut monograph, The Art of Place: Architecture and Interiors (Rizzoli). Of the 13 residences it contains, two are his own, and both qualify as master classes in decorating. Of particular note is the landmarked compound of interconnecting courtyards and pavilions in the Uptown district of New Orleans — designed in the 1960s by Nathaniel “Buster” Curtis — where Ledbetter currently lives with his husband, Douglas Meffert. Ledbetter reconfigured the house’s layout to dramatic effect but with characteristic respect, clarifying rather than disturbing Curtis’s original intentions. Designed around Curtis’s built-in cabinetry and Ledbetter’s extensive collection of studio ceramics, the decor mixes antique, mid-century and period furnishings. The shades of the faded carpets and jewel tones of the upholstery reflect the walnut hues of the existing millwork and the vivid hues of the sky, clouds and live oaks visible through the clerestory windows.

Ledbetter recently spoke with Introspective about his new book and his unique vision.

How did you pick The Art of Place as the monograph’s title?

I’ve always split my practice between interior design and architecture, so for a while, I was in favor of calling it The Dualist, borrowing the headline of an article Mayer Russ once wrote about me in House & Garden. But that word can be associated with deception. We tossed around five other titles and settled on The Art of Place because so many of its potential connotations are applicable to what I do. The phrase could refer to designing the identity of somewhere intimate as well as situating a building within the context of a region. If you play with the word order, it alludes to placing art, a place for art, an artful place. And then, hopefully, it posits architecture as one of the fine arts, which I firmly believe to be true.

Paintings by Regina Scully (left) and Mark Beard face each other in the living area of the Garden District house. At the back right are a pair of painted French fauteuils. The upholstered armchair in the foreground is by T. H. Robsjohn-Gibbings.

Sculpture has been described as “architecture without function,” but is it controversial to refer to architecture as a form of art?

I don’t think so. All of my early, basic art-appreciation studies focused on the historical parallels between painting, sculpture and architecture. But let me qualify that: I don’t consider building to be an art, and in my mind, architecture is something other than building. Like all things, though, it’s subjective. It would be more controversial to refer to interior design as a fine art. By extension, however, maybe it is? Whether yes or no, I think it’s a conversation worth having.

The book features two of Ledbetter’s own homes, including his 1960s Nathaniel ‘Buster’ Curtis–designed compound in the Uptown district of New Orleans. In the breakfast room, Ledbetter arranged Ion chairs by Gideon Kramer around the Isamu Noguchi table and placed a Pierre Jeanneret Scissor chair next to an Eero Saarinen Tulip side table.

Are there two types of architects, those who design around furniture and those who design spaces that will subsequently contain furniture?

I would say yes. To me, decorating is such a part of architecture, I could never isolate one from the other. By working with Robert A.M. Stern, I learned to place furniture in initial sketches and client presentations to immediately establish a sense of scale. It also tests how a space best serves the lives of the people who’ll inhabit it. It dictates how they’ll walk through a room, where they’ll sit to take in a view, how they’ll gather with friends. There’s obviously a precedent of architects designing interiors, but that training isn’t universal.

In your projects, you bring the past into the here and now by refusing to distinguish between modernism and historicism.

I admire a beautifully designed, well-crafted, well-conceived modernist building as much as anyone. At the same time, in New Orleans, I have access to a rich inventory of regional architecture representing a host of different periods, styles and materials, and I’m comfortable remaining open to them all. In that context, labeling myself as a modernist feels restrictive. And there’s no fear of clients’ associating me with purely traditional work. They come to me for excellence in design and construction, so from project to project, I’ve been able to remain true to myself.

Much of your decor is as restrained as it is layered with pattern and texture.

That stylistic combination isn’t a goal of mine, and it doesn’t always happen. In certain projects, the layering of colors and patterns in wallpaper, carpets and textiles feels organic and appropriate, but it all depends on the client’s background. I’m an egalitarian decorator. I reject all rights and wrongs and all theoretical rigidity. I’m not one of those architects who sticks with the classic, iconic Barcelona chairs and LC2s. That’s too predictable for me. I’m as uncomfortable with that type of dogmatism as I am with religious fundamentalism. There’s such a richness and history to antiques, why turn your back on that?

The Uptown residence has several courtyards. This one, off the dining room, impresses with a flower-petal patio original to the house.

Your design purview extends to landscaping. Was that always the case?

Yes. That goes way back, to the homes in which I grew up in the South. Their formal, symmetrical layouts were oriented to the exterior, and thanks to the luxurious, sub-tropical weather, a lot of my childhood was spent outside. It’s all still imprinted on my brain — everything canopied by large magnolia trees and live oaks, so houses were absolutely connected to their settings. I always work in tandem with landscape architects because I have strong preconceptions when I design a site plan. I know the effect I want, and I’m able to convey it, even though I don’t necessarily have the vocabulary or the horticultural experience to pick the plants.

You’re quite adept at incorporating clients’ personal belongings into your schemes.

In an honest partnership between designer and homeowner, clients want us to tell them what we don’t like or what doesn’t work. I’ve learned to embrace personal collections, even when they’re not particularly my taste, and by now it’s a heartfelt process. I like my projects to tell a story and feel inhabited. I want them to reflect the owners’ personalities and individuality.

Left: In the Garden District master suite, a Venini chandelier and an artwork by Marcel Ceuppens hang over the bed; the gunmetal-glazed ceramic lamps are by Pamela Sunday. Right: In the home’s breakfast room, a vintage Brazilian bar cabinet sits below a print by an unknown Cuban artist.

If a collection of art is a Rorschach test for its owner, what do the paintings and photographs you choose to live with say about you?

Rorschach is a perfect word, because I’m drawn to abstract art for all the different things I’m able to read into it. My passion for photography came through my close friend Margaret Sartor and her husband, Alex Harris. They are both photographers, he a protégé of Walker Evans. When I was younger and photography’s affordability was particularly appealing, I responded to abstracted imagery straightaway. I zeroed in on expressionists like Aaron Siskind, then fast-forwarded to Hiroshi Sugimoto’s primordial seascapes. I have one of Lynn Davis’s icebergs, as well as works by Wolfgang Tillmans, James Casebere, Tim Davis and Sally Gall. I own a remarkable piece, a monumental triptych shot by Jungjin Lee when she was inside a cave looking up at the sky.

As part of his dramatic reimagining of a mid-19th-century house in the New Orleans Garden District, Ledbetter removed walls below and in front of a staircase to create a free-floating effect and allow its sinuous curves to be seen from the living room.

You studied painting and architecture. Is that one of the reasons you enjoy designing spaces around artwork?

Painting and drawing are all about finding a focus while you stay loose and free. Architectural drafting is the exact opposite: It’s all straight edges, parallel lines and precision. I was encouraged to paint physically, to use my entire body, especially when I was working on a large scale. But drafting required me to home in and be detail oriented, which I eventually learned to appreciate. The beauty of the different line weights, the heavy and light layers — it all led to my love of graphic design. I’m privileged to work with clients who share my passion for art, whether I’m helping them flesh out their collection or deciding how and where to hang what they already own. I enjoy the process so much because I can’t imagine living in a room where there’s no art.

Your sense of aesthetics is strongly tied to nature, isn’t it?

When I think about beauty, I look to nature and see how it juxtaposes the organized and symmetrical with the unresolved and crude. There’s a parallel to that in my work. I’m pretty intuitive about finding the balance between order and the potentially disparate — something refined paired with something primitive particularly appeals. A room where everything is on the same aesthetic level is the equivalent of a person with a limited vocabulary. When every element in a room is of equal interest or weight, when there’s nothing to throw it off, it becomes generic, even when the pieces are extraordinary.

Posted on Thursday, March 28th, 2019 at 8:01 pm. Filed under: Commentator RSS 2.0 feed.

New Orleans’ Lee Ledbetter Makes Design Magic by Mixing Past and Present

Introspective Magazine / March 24, 2019

BY Linda O’Keeffe

The Louisiana-born and -bred architect talks to 1stdibs about the art of making timeless places that matter.

A new Rizzoli monograph from New Orleans–based architect and interior designer Lee Ledbetter shows off 13 of his residential projects (portrait by Henrik A. Knudsen). Top: In the den of a home in the Crescent City’s Garden District, Ledbetter flanked a custom mohair sofa with a pair of Edward Wormley swivel chairs and a pair of Harvey Probber bolster chairs (all photos by Pieter Estersohn, unless otherwise noted).

Lee Ledbetter defies categorization. An architect with serious credentials — he studied at the University of Virginia and Princeton and worked at Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, Michael Graves and Gwathmey Siegel — he refuses to be confined to one aesthetic. His houses are born from the immediate environment and greater region in which they are situated and react to local vernaculars rather than reject them. When Ledbetter dons his preservationist hat, he respects a building’s previous lives even as he brings them into dialogue with the present. The results are refreshingly unique.

His fluency in modernism and classicism, his reverence for historical precedents, his cosmopolitan perspective and willingness to submit to the pull of his Louisiana heritage — he was born and raised in the state and has run his studio from New Orleans for two decades — all qualify him as one of the country’s most accomplished, innovative and successful architectural practitioners.

Ledbetter also decorates his clients homes, creating layouts in which he often juxtaposes mid-century furniture by T. H. Robsjohn-Gibbings, Edward Wormley, Milo Baughman, William Haines and Harvey Probber with timeworn antique rugs, graphic textiles and muscular ceramics. He’s open to all periods, proclivities and provenances, and so his decor can be spare or sumptuous, laid-back or exuberant. He’s as likely to showcase contemporary art with a minimalist, Halston-inspired palette as he is to layer antiques with patterned textiles and wallpaper.

If Ledbetter has a signature, it’s the sense of spaciousness he injects into his rooms. His portfolio is full of wide thresholds, coffered ceilings, plays on scale, expansive color combinations and walls bathed in light. Many of his interiors are also characterized by a bias toward symmetry, the prominence of art (he’s both a trained painter and an avid collector) and a preference for comfort, elegance and panache.

Baker chairs in walnut surround a Matthew Hilton table in the dining area of the Garden District house. A large 19th-century giltwood mirror helps disperse light from a Lindsey Adelman chandelier and French contemporary brass sconces.

Ledbetter’s broad, spirited approach is on display in his recently released debut monograph, The Art of Place: Architecture and Interiors (Rizzoli). Of the 13 residences it contains, two are his own, and both qualify as master classes in decorating. Of particular note is the landmarked compound of interconnecting courtyards and pavilions in the Uptown district of New Orleans — designed in the 1960s by Nathaniel “Buster” Curtis — where Ledbetter currently lives with his husband, Douglas Meffert. Ledbetter reconfigured the house’s layout to dramatic effect but with characteristic respect, clarifying rather than disturbing Curtis’s original intentions. Designed around Curtis’s built-in cabinetry and Ledbetter’s extensive collection of studio ceramics, the decor mixes antique, mid-century and period furnishings. The shades of the faded carpets and jewel tones of the upholstery reflect the walnut hues of the existing millwork and the vivid hues of the sky, clouds and live oaks visible through the clerestory windows.

Ledbetter recently spoke with Introspective about his new book and his unique vision.

How did you pick The Art of Place as the monograph’s title?

I’ve always split my practice between interior design and architecture, so for a while, I was in favor of calling it The Dualist, borrowing the headline of an article Mayer Russ once wrote about me in House & Garden. But that word can be associated with deception. We tossed around five other titles and settled on The Art of Place because so many of its potential connotations are applicable to what I do. The phrase could refer to designing the identity of somewhere intimate as well as situating a building within the context of a region. If you play with the word order, it alludes to placing art, a place for art, an artful place. And then, hopefully, it posits architecture as one of the fine arts, which I firmly believe to be true.

Paintings by Regina Scully (left) and Mark Beard face each other in the living area of the Garden District house. At the back right are a pair of painted French fauteuils. The upholstered armchair in the foreground is by T. H. Robsjohn-Gibbings.

Sculpture has been described as “architecture without function,” but is it controversial to refer to architecture as a form of art?

I don’t think so. All of my early, basic art-appreciation studies focused on the historical parallels between painting, sculpture and architecture. But let me qualify that: I don’t consider building to be an art, and in my mind, architecture is something other than building. Like all things, though, it’s subjective. It would be more controversial to refer to interior design as a fine art. By extension, however, maybe it is? Whether yes or no, I think it’s a conversation worth having.

The book features two of Ledbetter’s own homes, including his 1960s Nathaniel ‘Buster’ Curtis–designed compound in the Uptown district of New Orleans. In the breakfast room, Ledbetter arranged Ion chairs by Gideon Kramer around the Isamu Noguchi table and placed a Pierre Jeanneret Scissor chair next to an Eero Saarinen Tulip side table.

Are there two types of architects, those who design around furniture and those who design spaces that will subsequently contain furniture?

I would say yes. To me, decorating is such a part of architecture, I could never isolate one from the other. By working with Robert A.M. Stern, I learned to place furniture in initial sketches and client presentations to immediately establish a sense of scale. It also tests how a space best serves the lives of the people who’ll inhabit it. It dictates how they’ll walk through a room, where they’ll sit to take in a view, how they’ll gather with friends. There’s obviously a precedent of architects designing interiors, but that training isn’t universal.

In your projects, you bring the past into the here and now by refusing to distinguish between modernism and historicism.

I admire a beautifully designed, well-crafted, well-conceived modernist building as much as anyone. At the same time, in New Orleans, I have access to a rich inventory of regional architecture representing a host of different periods, styles and materials, and I’m comfortable remaining open to them all. In that context, labeling myself as a modernist feels restrictive. And there’s no fear of clients’ associating me with purely traditional work. They come to me for excellence in design and construction, so from project to project, I’ve been able to remain true to myself.

Much of your decor is as restrained as it is layered with pattern and texture.

That stylistic combination isn’t a goal of mine, and it doesn’t always happen. In certain projects, the layering of colors and patterns in wallpaper, carpets and textiles feels organic and appropriate, but it all depends on the client’s background. I’m an egalitarian decorator. I reject all rights and wrongs and all theoretical rigidity. I’m not one of those architects who sticks with the classic, iconic Barcelona chairs and LC2s. That’s too predictable for me. I’m as uncomfortable with that type of dogmatism as I am with religious fundamentalism. There’s such a richness and history to antiques, why turn your back on that?

The Uptown residence has several courtyards. This one, off the dining room, impresses with a flower-petal patio original to the house.

Your design purview extends to landscaping. Was that always the case?

Yes. That goes way back, to the homes in which I grew up in the South. Their formal, symmetrical layouts were oriented to the exterior, and thanks to the luxurious, sub-tropical weather, a lot of my childhood was spent outside. It’s all still imprinted on my brain — everything canopied by large magnolia trees and live oaks, so houses were absolutely connected to their settings. I always work in tandem with landscape architects because I have strong preconceptions when I design a site plan. I know the effect I want, and I’m able to convey it, even though I don’t necessarily have the vocabulary or the horticultural experience to pick the plants.

You’re quite adept at incorporating clients’ personal belongings into your schemes.

In an honest partnership between designer and homeowner, clients want us to tell them what we don’t like or what doesn’t work. I’ve learned to embrace personal collections, even when they’re not particularly my taste, and by now it’s a heartfelt process. I like my projects to tell a story and feel inhabited. I want them to reflect the owners’ personalities and individuality.

Left: In the Garden District master suite, a Venini chandelier and an artwork by Marcel Ceuppens hang over the bed; the gunmetal-glazed ceramic lamps are by Pamela Sunday. Right: In the home’s breakfast room, a vintage Brazilian bar cabinet sits below a print by an unknown Cuban artist.

If a collection of art is a Rorschach test for its owner, what do the paintings and photographs you choose to live with say about you?

Rorschach is a perfect word, because I’m drawn to abstract art for all the different things I’m able to read into it. My passion for photography came through my close friend Margaret Sartor and her husband, Alex Harris. They are both photographers, he a protégé of Walker Evans. When I was younger and photography’s affordability was particularly appealing, I responded to abstracted imagery straightaway. I zeroed in on expressionists like Aaron Siskind, then fast-forwarded to Hiroshi Sugimoto’s primordial seascapes. I have one of Lynn Davis’s icebergs, as well as works by Wolfgang Tillmans, James Casebere, Tim Davis and Sally Gall. I own a remarkable piece, a monumental triptych shot by Jungjin Lee when she was inside a cave looking up at the sky.

As part of his dramatic reimagining of a mid-19th-century house in the New Orleans Garden District, Ledbetter removed walls below and in front of a staircase to create a free-floating effect and allow its sinuous curves to be seen from the living room.

You studied painting and architecture. Is that one of the reasons you enjoy designing spaces around artwork?

Painting and drawing are all about finding a focus while you stay loose and free. Architectural drafting is the exact opposite: It’s all straight edges, parallel lines and precision. I was encouraged to paint physically, to use my entire body, especially when I was working on a large scale. But drafting required me to home in and be detail oriented, which I eventually learned to appreciate. The beauty of the different line weights, the heavy and light layers — it all led to my love of graphic design. I’m privileged to work with clients who share my passion for art, whether I’m helping them flesh out their collection or deciding how and where to hang what they already own. I enjoy the process so much because I can’t imagine living in a room where there’s no art.

Your sense of aesthetics is strongly tied to nature, isn’t it?

When I think about beauty, I look to nature and see how it juxtaposes the organized and symmetrical with the unresolved and crude. There’s a parallel to that in my work. I’m pretty intuitive about finding the balance between order and the potentially disparate — something refined paired with something primitive particularly appeals. A room where everything is on the same aesthetic level is the equivalent of a person with a limited vocabulary. When every element in a room is of equal interest or weight, when there’s nothing to throw it off, it becomes generic, even when the pieces are extraordinary.

Posted on Thursday, March 28th, 2019 at 8:01 pm. Filed under: Commentator RSS 2.0 feed.

Widescreen WordPress Theme by Graph Paper Press All content © 2024 by Linda O'Keeffe